“Certain things are left up to the people who are writing the history, so certain things don’t make the narrative,” says playwright Reginald André Jackson.

Until now.

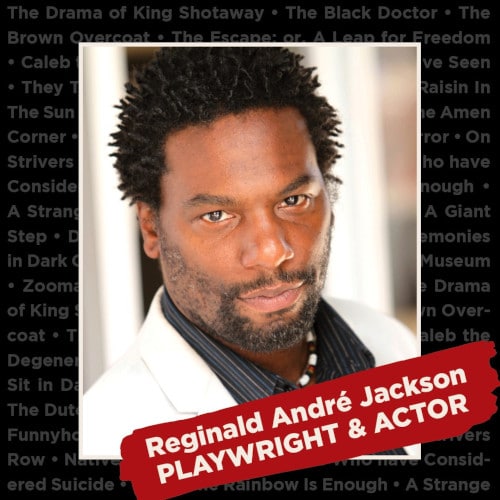

Enter actor turned playwright Reginald André Jackson. By his own admission, he’s not a historian, and yet he did and continues to write the history of theatre — specifically, Black theatre.

Influenced by the We See You, White American Theater and Black Lives Matter movements, Jackson is uncovering the untold stories of the past, turning the lives and words of Black theatre artists into a contemporary play, History of Theatre. Jackson shared, “The idea [for the play] is to look at the issues Black theatre artists have had historically, and as we come back into the theatre after the pandemic, we can learn and adjust so we don’t keep doing the same things.”

Jackson, admittedly, wasn’t initially sold on writing this history — or history at all. “It wasn’t my idea. I mean, when ACT came to me and said ‘the history of theatre,’ I was like, ‘What, ummm no…’ I didn’t know how to wrap my mind around all of it. When they added that it was about the history of Black theatre in the United States, it made it a bit smaller… though still huge.”

And so the playwright did what anyone would do: he dug into research — while libraries were shut down during the pandemic. This proved to be quite the challenge for Jackson, as many of the stories he sought to tell and/or uncover were so obscure that an internet search would not suffice.

Even as the libraries started opening back up, the challenge persisted. “I had an easier time finding information about Black people in the theatre some two hundred years ago than people from the ’60s right here in Seattle,” he said. And regardless of the time period, the tragic reality remained that some of that history just wasn’t documented. “It’s something we just know has happened to minority groups.”

While Jackson was deep in research during the summer and into the fall last year, he eventually began crafting what was, at that time, designed to be a documentary-style piece. “This was originally conceived as a curation, with me doing my best Walter Cronkite or Oprah Winfrey, looking up these people, using their words as much as humanly possible, and bringing to life an interview-style work.” But it started to become clear that, despite his best efforts, Jackson’s research was yielding relatively (and disappointingly) few direct quotes from history.

A new direction had to be explored. “The materials Reggie pulled together were powerful,” said director Valerie Curtis-Newton. “We decided that the stories he wrote were so strong that they were meant to be told as a fully developed play.”

“I began to manufacture a scene and put the characters in conflict and conversation around a specific topic or event,” Jackson added, and with that, the decision was made. “This also meant going back and starting at square one and rewriting everything in a totally different style.”

While two-hundred-plus years of history might seem daunting to some, the artistic team made the wise decision to cut the work into parts. “Part Zero” is a general introduction to the concept and an overview of the whole piece. “Part One” will take audiences from the African Grove Theatre through the Federal Theatre Project.

From there, “Part Two” will pick up in the 1960s and live as an ever-evolving history book, as the team works with Black theatre artists to continue to evolve and rewrite the narrative. In fact, Jackson is rather excited by the possibility of “interviewing living artists and using their words” to tell this story.

But the goal of this work is much bigger than a single cultural narrative. Part of what drew Jackson to it is its ubiquitous nature. “I hope that this can inspire someone else to take on the mantle and be the voice for others. That we can someday do History of Theatre and look at it from an Asian perspective or a Latin perspective. This is sort of looking into the future, but that would be the wish — that we can learn from and about so many different cultures.”

Taking into account all of the countless hours of research, a full pivot in the storytelling of the piece, and all of the writing and revising that has gone into its creation, Jackson reflected on what has made him most proud. “I don’t know how much credit I can take for what I am most proud of, but it is seeing the characters actually come to life and getting caught up in what the actors are experiencing, and knowing that we are sharing these stories and giving information. And when you bring in brilliant actors, they come in and take the breadcrumbs you give them and they create the magic.”

Writers don’t usually get involved in the casting of a show, but as Jackson explained, “I knew that I wanted to have people who also had a lived experience in this with me. That they would have this history, too.” Almost everyone working on the History of Theatre production is a result of the relationships that Jackson’s warm personality cultivated over his many years in the theatre. At the end of the day, that is what matters. “I wanted voices of people I trusted and enjoyed working with.”

As theatre-goers across the country settle in to watch the launch of History of Theatre, Jackson very much wants them to know this: “Many of the artists that came before us and the Black-run theatres were really doing it, and in ways we might even find hard to imagine. Just know, there is history here.”

So, while Reginald André Jackson might not be a “historian,” he is clearly rewriting the history books of yesterday, the narratives of today, and the hopes for tomorrow, one scene, one conversation, and one chapter at a time.