On Death of a Salesman

A play by Arthur Miller

THE CHARACTERS

Willy Loman, a traveling salesman who clings to the American dream of success, wealth and legacy

Linda Loman, Willy’s faithful wife whose support of her husband masks her own perceptive nature

Biff Loman, Willy’s adult son who, after his glory days in high school, cannot seem to find success

Happy Loman, Willy’s adult son who spent his childhood in his older brother Biff’s shadow

Charley, a successful business owner and Willy’s neighbor

Bernard, Charley’s son and Biff’s former classmate

Uncle Ben, Willy’s older brother and a self-made man of success and wealth. Ben is dead though Willy talks to him throughout the play.

The Woman, Willy’s mistress

Howard Wagner, Willy’s boss

Jenny, Charley’s secretary

Stanley, a waiter

Miss Forsythe and Letta, two young women

SYNOPSIS

Willy Loman lives in Brooklyn with his wife Linda and two grown sons, Biff and Happy. He’s a salesman who’s spent his whole life following the rules. He’s raised his sons to believe that if they also follow the rules, they can make something of themselves. But Willy has come to realize that his life might have been a failure. His dreams for himself and sons are crumbling. Biff can’t keep a job. Happy isn’t exactly, well, happy. Willy and Linda struggle to make payments on their old house that’s surrounded by newer apartment buildings.

In order to deal with the failures of his life, Willy escapes by remembering the past and fantasizing about how things could have been. In doing so, he loses touch with reality and makes plans to commit suicide. His family tries to prevent it by enabling Willy’s fantasies and lying to him.

One day—and after working his whole life for the same company—Willy loses his job and gets desperate. He’s been arguing with Biff and can’t accept that Biff doesn’t want to be a businessman. Even worse, Willy can’t face the fact that his own life has been a disappointment. As the play reaches its conclusion, the audience is left to consider an important question: What does a man do when he considers his life to be a failure?

ON REALITY VS. ILLUSION

The gap between reality and illusion is blurred in the play—in the structure, in Willy’s mind, and in the minds of the other characters. Willy is a dreamer and dreams of a success that it is not possible for him to achieve. He constantly exaggerates his success: (“I averaged a hundred and seventy dollars a week in the year of 1928”) and is totally unrealistic about what Biff will be able to achieve too. Willy’s inability to face the truth of his situation, that he is merely “a dime a dozen,” rubs off on his sons. Happy exaggerates how successful he is, and Biff only realizes in Oliver’s office that he has been lying to himself for years about his position in the company: “I realized what a ridiculous lie my whole life has been. We’ve been talking in a dream for fifteen years. I was a shipping clerk.” Biff is the only one who realizes how this blurring of reality has destroyed them all. His aim becomes to make Willy and the family face the truth which they have been avoiding, the truth of who they are: “The man don’t know who we are!… We never told the truth for ten minutes in this house.” This blurring of reality and illusion is carried through into the structure.

HISTORY OF THE PLAY

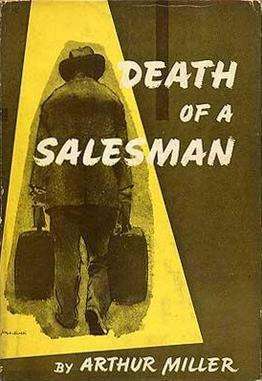

Death of a Salesman is a stage play written by the American playwright Arthur Miller. The play premiered on Broadway in February 1949, running for 742 performances. It is a two-act tragedy set in late 1940s Brooklyn told through a montage of memories, dreams, and arguments of the protagonist Willy Loman, a traveling salesman who is despondent with his life and appears to be slipping into senility. The play addresses a variety of themes, such as the American Dream, the anatomy of truth, and infidelity. It won the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and Tony Award for Best Play. It is considered by some critics to be one of the greatest plays of the 20th century.

Since its premiere, the play has been revived on Broadway five times, winning three Tony Awards for Best Revival. It has been adapted for the cinema on ten occasions, including a 1951 version by screenwriter Stanley Roberts, starring Fredric March. In 1999, New Yorker drama critic John Lahr said that with 11 million copies sold, it was “probably the most successful modern play ever published.”

Original Death of a Salesman cover

ARTHUR MILLER ON DEATH OF A SALESMAN

Photo of Arthur Miller by Eric Koch

“Willy resents Linda’s unbroken, patient forgiveness (knowing there must be great hidden hatred for him in her heart.”

-Miller’s Death of a Salesman Notebook chronicling the play’s creation (source: The New Yorker)

“Willy is foolish and even ridiculous sometimes. He tells the most transparent lies, exaggerates mercilessly, and so on. But I really want you to see that his impulses are not foolish at all. He cannot bear reality, and since he can’t do much to change it, he keeps changing his ideas of it.”

-Arthur Miller, Salesman in Beijing, 1984

“I had known all along that this play could not be encompassed by conventional realism, and for one integral reason: in Willy, the past was as alive as what was happening at the moment, sometimes even crashing in to completely overwhelm his mind.”

-Arthur Miller from his 1987 autobiography, Timebends: A Life

“The curtain came down and nothing happened. People sat there a good two or three minutes, then somebody stood up with his coat. Several men—I didn’t see women doing this—were helpless. They were sitting there with handkerchiefs over their faces. It was like a funeral. I didn’t know whether the show was dead or alive. The cast was back there wondering what had happened. Nobody’d pulled the curtain up. Finally, someone thought to applaud, and then the house came apart.”

-Miller, speaking about the night of the play’s début, February 10, 1949, in Philadelphia.

Sources:

The New Yorker

The Weston Playhouse Theatre Company

REVIEWS OF THE PLAY

“As social drama, Death of a Salesman is a dud. Willy Loman’s crack-up is a personal rather than a social tragedy. His story is good drama, however—the play most likely to succeed when various committees distribute their medals and blue ribbons.

– Theophilus Lewis, April 9, 1949

“Arthur Miller has written a superb drama. It is so simple in style and so inevitable in theme that is scarcely seems like a thing that has been written and acted. For Mr. Miller has looked with compassion into the hearts of some ordinary Americans and quietly transferred their hope and anguish to the theatre. Death of a Salesman… becomes poetry in spite of itself….

Writing like a man who understands people, Mr. Miller has no moral precepts to offer and no solutions of the salesman’s problems. He is full of pity, but he brings no piety to it. Chronicler of one frowsy corner of the American scene, he evokes a wraith-like tragedy out of it that spins through the many scenes of his play and gradually envelops the audience.”

– Brooks Atkinson writing for The New York Times; February 11, 1949

“Death of a Salesman is dismally depressing, but it must be acclaimed a film that whips you about in a whirlpool somewhere close to the center of life. To relieve the depression somewhat, the program at the Victoria also boasts a perfectly marvelous little cartoon from the United Productions people, called “Rooty Toot Toot.” It is a deliciously sly and clever takeoff of the Frankie and Johnny tale, done with sophisticated drawings and mellow colors. It is a charm.”

–The New York Times on the 1951 film; December 21, 1951

“The tired old man has had an unexpected transfusion. And he has seldom seemed more alive — or more doomed. What’s most surprising about Marianne Elliott and Miranda Cromwell’s beautiful revival of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman is how vital it is. As Willy Loman, the title character of this epochal 1949 drama, lives out his last, despondent days, what has often felt like a plodding walk to the grave in previous incarnations becomes a propulsive—and compulsively watchable—dance of death.

Salesman has always been a study in cancerous denial, an interior portrait of a man long out of touch with who he is. (Miller had at first thought of calling his play “The Inside of His Head.”) This production finds the desperate exertion in such denial, the paradoxical energy in the exhaustion of playing a losing game for too many seasons.

In this Salesman, when Willy, in a rare moment of insight, says he feels “kind of temporary,” the terror that he ultimately owns nothing—not even his own identity—has never felt so profound.”

-Ben Brantley writing for The New York Times; January 2, 2020

“But it is not simply the dramatic contrivance and redundancy of scenes like this that mar the play; it is the crude psychological determinism that underwrites them. In Salesman there is always a straight line leading from a harrowing past event to a present neurosis or failure. Thus, the play contains no mysteries, only secrets. Characters are explained, exposed, insisted upon; but Miller rarely allows them to stray into the kind of tantalizing opacity and incoherence that makes the people in, say, Chekhov or Shakespeare seem so real.”

– from Death of a Salesman: A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Mediocrity by Giles Harvey for The New Yorker; May 14, 2012

Sources:

The New Yorker

The New York Times Archives

QUOTES FROM THE PLAY

LINDA (very carefully, delicately): Where were you all day? You look terrible.

WILLY: I got as far as a little above Yonkers. I stopped for a cup of coffee. Maybe it was the coffee.

————————-

WILLY: The boys in?

LINDA: They’re sleeping. Happy took Biff on a date tonight.

WILLY (interested): That so?

LINDA: It was so nice to see them shaving together, one behind the other, in the bathroom. And going out together. You notice? The whole house smells of shaving lotion.

————

WILLY: Figure it out. Work a lifetime to pay off a house. You finally own it, and there’s nobody to live in it.

LINDA: Well, dear, life is a casting off. It’s always that way.

WILLY: No, no, some people—some people accomplish something.

———

WILLY (stopping him): I’m talking about your father! There were promises made across this desk! You mustn’t tell me you’ve got people to see—I put thirty-four years into this firm, Howard, and now I can’t pay my insurance! You can’t eat the orange and throw the peel away—a man is not a piece of fruit!

————–

WILLY: You’ll retire me for life on seventy goddam dollars a week? And your women and your car and your apartment, and you’ll retire me for life! Christ’s sake, I couldn’t get past Yonkers today! Where are you guys, where are you? The woods are burning! I can’t drive a car!

————

WILLY (lost): More and more I think of those days, Linda. This time of year it was lilac and wisteria. And then the peonies would come out, and the daffodils. What fragrance in this room!

———–

BIFF: What’s he doing out there?

LINDA: He’s planting the garden!

BIFF (quietly): Now? Oh, my God!

(Biff moves outside, Linda following. The light dies down on them and comes up on the center of the apron as Willy walks into it. He is carrying a flashlight, a hoe, and a handful of seed packets. He raps the top of the hoe sharply to fix it firmly, and then moves to the left, measuring off the distance with his foot. He holds the flashlight to look at the seed packets, reading off the instructions. He is in the blue of night.)

WILLY: Carrots… quarter-inch apart. Rows… one-foot rows. (He measures it off.) One foot. (He puts down a package and measures off.) Beets. (He puts down another package and measures again.) Lettuce. (He reads the package, puts it down.) One foot — (He breaks off as Ben appears at the right and moves slowly down to him.) What a proposition, ts, ts. Terrific, terrific. ‘Cause she’s suffered, Ben, the woman has suffered. You understand me? A man can’t go out the way, he came in, Ben, a man has got to add up to something. You can’t, you can’t — (Ben moves toward him as though to interrupt.) You gotta consider, now. Don’t answer so quick. Remember, it’s a guaranteed twenty-thousand-dollar proposition. Now look, Ben, I want you to go through the ins and outs of this thing with me. I’ve got nobody to talk to, Ben, and the woman has suffered, you hear me?