“Dickens enters the theatre of the world through the stage door…” George Santayana

As a young man, Charles Dickens hoped to become an actor and actually got as far as scheduling an audition with one of London’s premier theatre managers. Unfortunately, on the day of the audition he came down with a bad cold and was unable to attend. Happily for English literature, if perhaps unhappily for the English stage (the evidence suggests that had Dickens become an actor, he’d have been second to none), Dickens didn’t pursue his acting ambitions further. However, he remained an avid theatre-goer, attending every week for the rest of his life, and participated enthusiastically in amateur theatricals of all kinds. The most famous of these was The Frozen Deep (1857), a melodrama set in the Arctic and written in collaboration with his friend Wilkie Collins (The Moonstone, The Woman in White). It was first performed in the schoolroom of Dickens’ house (re-christened “The Smallest Theatre in the World” for the occasion) with some of the windows and part of a wall removed to extend the stage – no doubt to the dismay of the playwright/star’s long-suffering wife!

Although fate led Dickens away from the professional stage, disarming theatrical characters turn up regularly in his novels — one thinks especially of his colorful and affectionate portrait of the itinerant Crummles Troupe in Nicholas Nickleby — and his own creative process as a writer included as much performance as penmanship. He approached all his books as if they were a kind of one-man theatrical extravaganza. His daughter Mamie remembered an afternoon when she was recovering after a long illness and as a special treat was allowed to stay in her father’s study while he wrote. Mamie lay on the sofa doing her best not to disturb him as he scribbled away — Dickens wrote at a tremendous clip — when suddenly he “jumped from his chair and rushed to a mirror which hung near, and in which I could see the reflection of some extraordinary facial contortions which he was making. He returned rapidly to his desk, wrote furiously for a few moments, and then went again to the mirror. The facial pantomime was resumed, and then turning toward, but evidently not seeing, me, he began talking rapidly in a low voice…With his natural intensity, he had thrown himself completely into the character he was creating, and for the time being he had not only lost sight of his surroundings, but had actually become in action, as in imagination, the personality of his pen. ”

The moment it was published in 1843, A Christmas Carol was seized upon by playwrights looking for a sure-fire success, and by February 1844 no fewer than eight stage adaptations could be seen on the West End – only one of them actually authorized by Dickens – but the most famous and most effective of the Carol’s stage performances were still some years off: those given by Dickens himself. He gave his first public reading of A Christmas Carol in 1853 at Birmingham before an audience of nearly 2000 people, an immense crowd for the time. The nervous author supervised the setting of the stage himself, barely hiding his displeasure at the box lectern that had been provided for him and which concealed him completely from the audience except for his head and shoulders. His actor’s sense told him that it was imperative for him to be able to use his whole body to establish different characters, and after that first performance (a rousing success, the box notwithstanding) he had his own lectern specially built, a sort of overgrown table with an armrest, slender-legged and about waist high. He also designed his own lights, and was one of the first people to use an overhead light-bar instead of the then more usual footlights, which cast heavy and sometimes distorting shadows upward onto an actor’s face. He even traveled with his own lighting technician, to insure that the gaslight bar would be hung properly and the effect just right.

Despite his raging popularity, in this century before radio and television very few of his devoted readers knew what Dickens looked like or sounded like, and the opportunity actually to see him in person and reading from his own work was an event not to be missed. Dedicated fans would camp in the street outside the auditorium the night before tickets went on sale, as if for a rock concert or the World Series, and although Dickens always made sure that some seats were priced within reach of the working class at just a shilling each, tickets were scalped regularly at prices far in excess of their face value.

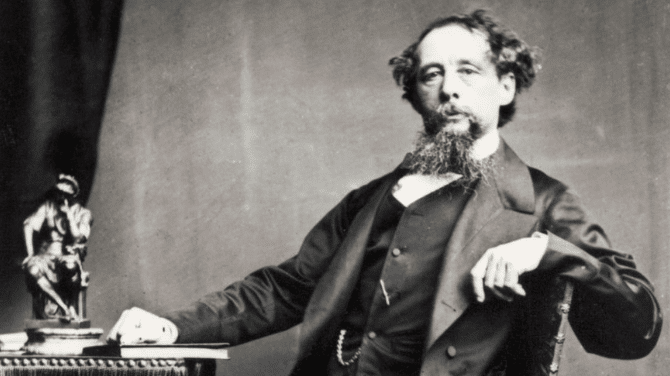

And what did they see, these people who waited all night on the pavement? Many in his audience were, at first, disappointed. Dickens was not an imposing figure physically, nor did he have the commanding vocal range of the most notable public speakers of the day. Still, he carried himself well and with a certain panache; what his voice lacked in scope it more than made up in flexibility, resonance and color; and once he began to read, people soon forgot their initial reservations. Beyond his undoubted gifts as an actor, Dickens also had enormous charisma, and an ability to enthrall an audience through sheer force of personality that we would describe now as “star quality.” Eyewitnesses describe the energy of his movements as he walked briskly to the podium, his marvelously mobile and expressive face, and most of all the twinkle in his large, deeply set brown eyes as he announced in his rapid, emphatic way “Marley-was-dead-to-begin-with…”, as if he were already anticipating the thrills and delights of the story he was about to tell and could hardly wait to get on with it.

After the Birmingham reading, he no longer read the entire original text, but a special version he created particularly for performance: a script. It omitted not only chunks of narrative and character description, much of which was supplied by Dickens’ own portrayal of the various characters, but also, surprisingly, Christmas Present’s revelation of the tattered children Ignorance and Want, emphasizing the story’s holiday message over the social commentary that had been one of his primary reasons for writing it. Presumably Dickens felt that the emotional, human content of the story would be most effective for a live audience; in this forum, his mandate was to entertain, not to preach. An American journalist wrote that to hear Dickens read the Carol was like hearing the very sound of Christmas bells, and in time the readings became a holiday tradition for many people — just as families now go every year to see “The Nutcracker,” or watch Frank Capra’s American gloss on A Christmas Carol, “It’s A Wonderful Life.”

It’s not unusual for artists to be gifted in more than one way, but what was unusual about Dickens was the degree to which his two talents were enmeshed. What the writer’s imagination conceived, the actor vitalized in solitary performances that the writer translated into literature, which the actor then returned to three dimensions in the many readings from his work that Dickens gave in the final decade of his life. The process also worked in reverse: playing the role of The Frozen Deep’s conflicted anti-hero, who sacrifices himself to save the life of his romantic rival, directly inspired Dickens to create one of his most indelible characters, the dissolute but ultimately noble Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities. The connective tissue between a writer and an actor, of course, is the drive to tell a story, but writers tell theirs alone, for an audience they can only imagine and may never see. What joy it must have been for Dickens to stand on stage and see the impact of his stories in real time, on the faces of his audiences! It’s interesting to note that there are no quotes from him about his writing as vibrant as this one about acting: “I would like to be going all over the kingdom,” he burst out one night after a particularly successful performance, “and acting everywhere! There is nothing in the world equal to seeing the house rise at you, one sea of delighted faces, one hurrah of applause!”

So gather round with us again to listen to what Dickens’ great-granddaughter Monica called “the greatest little book in the world,” and join us and our actors in celebrating the joys of the season and one of the greatest storytellers who ever lived – off the stage and on it.

— Margaret Layne

Margaret Layne is ACT’s Director of Casting. She holds a B.A Cum Laude in English Literature from Yale University.